11.1 – Poker face

Last month I got an opportunity to play poker with a few good friends. I was playing poker after a gap of 6 years and I was quite excited about it. The buy in for this friendly game was Rs.1000/. For those who are not familiar with poker – it’s a card game where in your skill and luck are tested in equal measure.

So, the game started, cards were dealt, and in the very first round I bet Rs.200/- and I saw it go away, just like that. In the next round, I bet another 200, and again saw it go away. At this stage I convinced myself that I could make up my losses in the 3rd round, and with this thought I increased the bet size to 600, only to watch it go away! So for all practical purposes, I lost Rs.1000/- in a matter of 10 minutes! In the trading world, this is equivalent to blowing up your entire trading account.

I didn’t give up, after all, I’m supposed to know trading and poker draws many similarities to trading. I decided to ‘recover’ my initial loss and stay in the game longer. I bought in for another 1000 and started fresh. This time, I stayed on the table a bit longer – for a total of 15 minutes!

Clearly, it was not working for me. I had a better memory of me playing poker 6 years ago. Though not the best, at least, I would stay on the table till the game lasted and even win few hands. So what was happening this time around? I was confused and I kind of didn’t believe that this was happening to me? How could I wipe my account twice in a matter of 25 minutes?

With these confusing thoughts on my past poker skills and my current game play, I decided to buy in again for another 1000 Rupees. This was my 3rd buy in. In the trading world, this is equivalent to funding your account 3rd time over after successfully blowing it up twice.

What advice would you give someone who has blown up his account twice in the markets? – ‘get out of the markets immediately’, would perhaps be the best-suited advice right? Well, I dint pay any heed to my inner voice, gambler’s fallacy had taken over my rational thinking abilities and I bought in again for 1000 Rupees more.

For those of you who don’t know gambler’s fallacy – if you are betting on an outcome and you tend to make a long streak of losses, then at the time of quitting, your mind tells you or rather tricks you to believe that your losing streak is over and your next bet will be a winner. This is when you increase your betting size and lose a bigger chunk of money. Gamblers fallacy is one of the biggest culprits in wiping out many trading accounts clean.

Anyway, back to my poker game. This was my 3rd buying, I had already lost 2K and was betting with another 1K. I was confident I’d recover plus make some money and save myself some shame, but the boys on the table had other plans for me. They knew I was the sucker on the table and it was easy to allure me to make irrational bets. So they did and wiped me out clean over the next 7 minutes.

That was it, I called it quits and I got back more after losing 3k.

After the game, I thought through on what went wrong. The answer was very clear –

- I had forgotten to recognize the odds of winning with the cards that were dealt

- I was not ‘position sizing’ my bets – my bets were way too irrational and random

After a couple of weeks, I had another invite to the game. I had set a bad precedence of giving away easy money. This time around I had decided to position size my bets well.

I bought in for 1000 and started the game. Each time the cards were dealt – I accessed my odds fairly well and if I thought my odds were fair, I bet accordingly. In the trading world, this was equivalent to following a ‘trading system’ backed by position sizing techniques. The result of this simple systematic approach had a great impact on my game –

- I won few hands

- At the peak, I must have had about 4K of winnings

- I lasted throughout the game and had a lot of fun along the way

- Towards the end I gave up some gains but was extremely happy with the fact that few simple techniques helped me manage my game much better

Position sizing made all the difference in this game. It always does and this is the exact reason for me to narrate this story. I do not want you to speculate in the markets without understanding your odds or without position sizing your bets. If you do, you will end up making a fool out of yourself.

Poker is played for fun but when you trade, you are essentially deploying your capital for a more serious and meaningful outcome. So please do pay attention to some of the things we will discuss over the next few chapters. I’m certain it will have a positive impact in your trading career.

At this point I have to mention this – I myself learned position sizing many years ago by reading Van Tharp’s books. Van Tharp is one of the most prominent people to bring in the concept of position sizing to traders. I’d even recommend you buy some of his books to expand your knowledge on this subject.

11.2 – Gambler’s fallacy

We briefly discussed the gambler’s fallacy early on. I guess it makes sense to discuss a little more on this at the very beginning especially in the context of markets.

Take a look at this chart –

This is the chart of Nifty – Nifty hit the magical number of 10,000 on 25th July 2017. As a trader, how would you trade this?

- Nifty is at an all-time high – 10K

- Many market participants may book profits at this point – considering it is a phycological level

- All time high implies no resistance points

- Nifty has been in a great up wards trend over the past few weeks

- Maybe Nifty would consolidate around these levels?

- Maybe a correction of 2-3% before the rally continues?

Let us just assume that these are some valid points for now. This means a short position is justified or for that matter buying of puts. Your analysis could be as simple as this or as sophisticated as studying the time series data and modeling the same using advanced statistical or machine learning models.

Irrespective of what you do – there is no certainty in the markets. No one technique will tell you the outcome in advance. This implies that we are dealing with fairly random draws here. Of course, based on how meaningful your analysis is, your odds of winning can improve, but at the end of the day, there is no certainty and you have to acknowledge the fact that markets are indeed random.

Now imagine this – you have done a state of the art analysis and you place your bet on Nifty only to see the stop loss trigger. You do not give up, you place another trade and to your misfortune, you are stopped out again. This cycle repeats for say the next 4 trades.

You know your analysis is bang on – but then your stop loss is continuously getting triggered. You still have money in your account to take on bets, you are still convinced that your analysis is rock solid and the markets will turn around, you still have an appetite for risk – given all these, what do you do?

- Would you stop trading?

- Would you risk the same amount of money again?

- Now that you have lost 6 consecutive bets, would you consider that your odds of making money on the 7th trade is higher and therefore increase your bet size to recover your previous losses plus reap in some profits?

Which option are you likely to take? Take a minute and answer this question honestly to yourself.

Having been through this situation myself and having interacted with many traders let me tell you – most traders would take the 3rd option, the question however is – why?

Traders tend to believe that long streaks will cease when they take the ‘next’ trade. For instance, in this case, the trader has faced 6 consecutive losses, but at this point his conviction that the 7 trade will be a winner is very high. This is called ‘Gambler’s fallacy’.

In reality, when you are dealing with random draws, the odds of making a loss on the 7th trade is as high (or low) as it was when you placed your first bet. Just because you have made a series of losses, the odds of making money on the next trade does not improve.

Traders fall prey to ‘Gamblers fallacy’ and often end up increasing their bet sizes without understanding how the odds stack up. In fact, gamblers fallacy ruins your position sizing philosophy and therefore is the biggest culprit in wiping out trading accounts.

This works on the other side as well. Imagine, that you are fortunate enough to witness a 6 or let us say 10 consecutive wins. Whatever you bet on, the trade works out in your favor. You are on your 11th trade now, which of the following are you likely to do?

- Considering that you made enough money, would you stop trading?

- Would you risk the same amount again?

- Would you increase your bet size?

- Will you take a conservative approach, maybe protect you profits, and therefore reduce your bet size?

Chances are that you will take the 4th option. You clearly want to protect your profits and do not want to give back whatever you have earned in the markets and at the same time you would want to take a trade considering you have had a great winning streak.

This is again ‘gamblers fallacy’ at play. Being completely influenced by the outcome of the previous 10 trades, you are essentially reducing your position size for the 11th trade. In reality, this new trade has a same odds of winning or losing as the previous 10 bets.

Perhaps, this explains why some of the traders, even though get into profitable trading cycle end up making very little money.

The antidote for ‘Gambler’s Fallacy’, is position sizing.

11.3 – Recovery trauma

In the trading world, the capital we bring on the table is the raw material. If you do not have enough money to trade with, then how will you make a profit? Hence we need to not just protect the profits that we make, but also protect the capital.

Extending this thought – if you risk too much capital on any one trade, then you stand a chance to risk your capital to an extent that you may burn your capital leaving you with very little money. Now if you are trading with very little money, then every trade that you take will appear to be too risky. The climb back to where you started will (in terms of capital) will be a Herculean task.

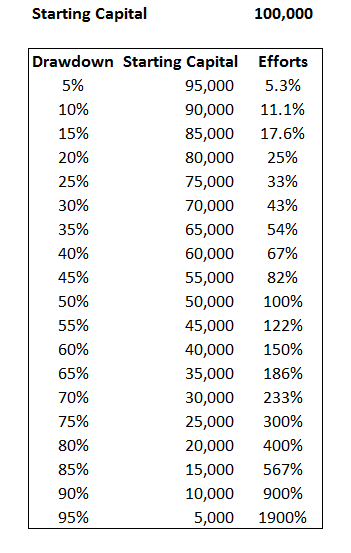

I have prepared a table to help you understand this fact. Assume you have a trading capital of Rs.100,000/-. Let us see how the numbers stack up with –

You can download the excel sheet here.

Assume you lose 5% of your capital or Rs.5000/-. Your new starting capital is Rs.95,000/-. Now, in order to recover to Rs.5000 with a capital of 95000, you need to generate a return of 5.3%, which is 0.3% more than what you lost.

Now, instead of 5%, assume you lost 10% and your capital becomes 90000, now in order to recover 10000 or 10% of your original capital, you have to earn back 11.1%. As you can see, as the loss deepens, you will have to work really hard to bounce back to original starting capital. For example at 60% loss or original capital, you are staring at a 150% bounce back.

Unfortunately, the ‘recovery trauma’ affects traders with smaller account size. Assume you come to the market with Rs.50,000/- capital. Now you would have heard of stories on how Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, grew his money from 10,000 to 15K Crores. You would want to replicate at least a small portion of this success. Honestly speaking, if you can manage to grow Rs.50,000/- to say Rs.60,000 by the end of the year, you would have done a great job. This translates to a 20% return. But this is not exciting, right? I mean earning Rs.10,000/- over 1 year when you are actively trading somehow does not seem right.

So what do you do? You tend to take bigger risks and hope to make bigger gains, and if the trade goes against you, then you are essentially falling prey to the ‘recovery trauma’ phenomena.

This is exactly the reason why you should never risk too much on any one trade, especially if you have a small capital. Remember, your odds of making good money in the markets is high if you can manage to stay in game for long, and to stay for a longer period, you need to have enough capital, and to have enough capital, you need to risk the right amount of money on each trade. This really boils down to working towards longer term ‘consistency’ in markets, and to be consistent you need to position size your trades really well.

I’m going to close this chapter with a quote from Larry Hite.

Over the next few chapter, we will dig deeper into position sizing techniques.

Key takeaways from this chapter

- Position sizing forms the corner stone of a trading system

- Gamblers fallacy is a bias highly applicable to the trading world. It makes the trader believe that a long streak of a certain outcome can break

- When there are infinite draws, the odds of making a profit or loss on the Nth trade is similar to the odds of making the same profit or loss on the 1st trade

- The recovery of capital is much more difficult task than one can imagine

- Traders with small accounts have a tendency to take larger bets, which they need to avoid

I sincerely believe in what Charlie Munger often says about

I sincerely believe in what Charlie Munger often says about